untitled speech 2017

The Bolivarian Revolution can be studied as a series of exemplary public gestures or “capital actions”: Lieutenant Hugo Chávez, facing the microphones on February 4th, 1992, delivering his famous “for now” speech that simultaneously admitted the defeat of the military coup and promised a return; the already elected president Chávez illuminated by hundreds of flashes swearing to uphold the Constitution that he had just declared “moribund”; the selfsame Chávez eating a cookie offered to him by a child at a rally; later, unveiling a painting with the new image of Simón Bolívar that emerged from a reconstruction process that seemed to have related him to the Liberator; and Chávez in a terminal state, bathed by the rain, in the middle of the feverish multitude, haranguing the slogans of his last electoral campaign.

In a sense, Chávez––his body––is the revolution. And the revolution, for Chávez, is always a performance of power. To execute this performance meant to centralize in himself––in his body––all of the institutionality, all of the strength, all of the decision, all of the affect. To carry out this performance was, for Chávez, to concentrate all of language itself in his tongue.

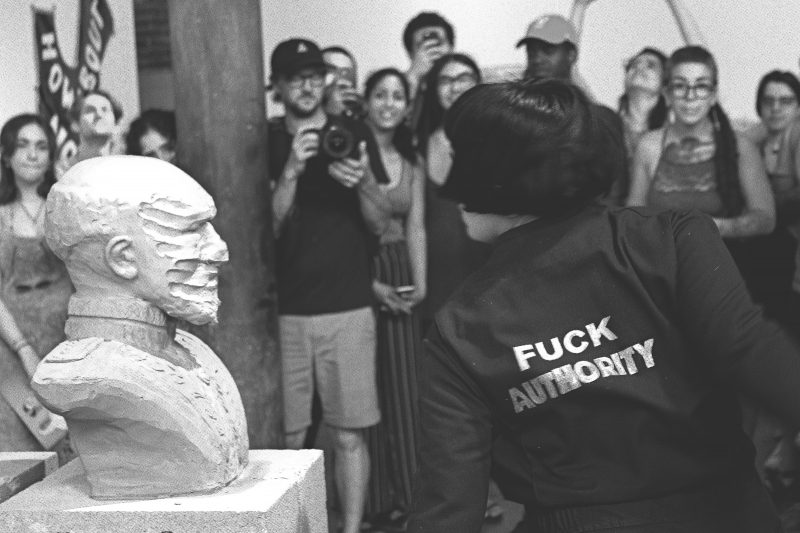

The critical potential of Deborah Castillo’s work consists in knowing how to oppose that language-producing tongue with another one: a material, organic, viscous, corrosive tongue. Faced with the materialization of the power of Chávez’s discourse, there it is: the rebellious power of Castillo, that power that does not want to be language, that does not want to be discourse, that does not want to be history. This tongue has licked everything in strict silence: shoes, books, a heroic bust…it has even licked words. A timid border separates the tongue from the bite, the pleasure from pain and the latter from the pleasure of inflicting pain. Castillo’s tongue bites, bites where it hurts, where it is no longer possible to distinguish fruition from friction, and affliction from disgust or rage. Against the performance of power, the power of performance: a rabidly singular action, covered in meaning, which faces the political manipulation of the notion of the “people,” under which citizens are deprived, precisely, of their ability to act.

Deborah Castillo was born in Caracas, Venezuela, and graduated from the Armando Reverón School of Plastic Arts. She has received numerous recognitions and artistic residencies throughout her career. Her work incorporates media–performance, sculpture, photo-novel, and video, and has been exhibited in many different countries, including Venezuela, the United States, France, Mexico, England, Spain, Bolivia, and Brazil. The essays that make up this volume focus on Castillo’s work from Lamezuela (2012) to Marx Palimpsest (2018); that is, from the exploration of an encounter between the body and military power (in the context of the Bolivarian Revolution), to the problematization (in a global context) of the process through which political philosophy becomes ideological manipulation.

That said, Castillo’s referential universe––always intertwined with Venezuela’s political crisis––is far broader. On the one hand, we have the unabashed irony of the Profunda Mol series, which narrates, through video art and photo-novel formats, the adventures of a woman who goes from cleaning art galleries to occupying the position of the Minister of Culture and, from there, to that of the First Lady of the United States. Likewise, Castillo’s tongue has licked/erased the insults received by Latin American women and immigrants in Europe and the United States. Her work has also turned the last appropriation of Bolívar (in Venezuela) into a sort of open question about the authoritarian turn of the Left worldwide, and the meaning, scope, and consequences of state Power when exercised by one man. This has given her work (and the way in which political power is represented in it) a global character, a broader circulation, especially throughout the rest of Latin America, where the heroic imagery works in other ways, where the figure of the authoritarian “milico”––a pejorative term for soldier––has its own traditions and awakens its own terrors.

Read as a whole, the essays that make up this volume propose a series of perspectives from which to analyze the work of Castillo. The Bolivarian Revolution is but one of them. Indeed, Castillo’s work highlights how, in the face of a new project of radical collectivization, the singularity of a body––her own––appears as a response and a challenge to the violence of the signifier “people.” The Bolivarian Revolution thus constitutes the repertoire to which Castillo constantly returns. From there, she extracts and deconstructs the figure of the hero in its various historical transfigurations. Beyond the Bolivarian Revolution, however, Venezuelan historiography has shown how, in the national imagination of this country, the hero of the Wars of Independence holds an enormous gravitational force. Castillo stages the multiple returns of that figure: the hero is not only the caudillo, but also the father of the nation and the weight of the nation in each singular body. When it comes to the people, that father who burdens is the lawgiver; when it comes to the leader, he is the giver of legitimacy and legibility. Through Castillo’s work, then, it can be seen how the specter of Bolívar reappears in the Bolivarian Revolution as it has done so many times before: embodied, hypermasculinized, doctrinaire. Faced by him, Castillo’s feminine body makes explicit––by ironizing, deactivating, challenging, eroticizing, and reconfiguring––both his power and his sacredness. This set of essays analyzes these operations. Thus, Radical Disobedience constitutes not only an effort to think about the work of the most important performance artist in Venezuela, but also to reflect on power, the body, and resistance.

This volume opens with the work of Alejandro Castro and his reading of Lamezuela (2012). Castro proposes three lines of reflection on this work. The first one focuses on the name of the performance and the role that language plays within it, a language which, in the words of Castro, “does not speak, suck, eat or stay still,” and allows us to think about what connects eroticism, reason, and violence withpower and political subjectivity. Castro’s second line of analysis considers the stencil that reproduces an image from Castillo’s performance, in which she kneels and licks the boots of a soldier. This stencil circulated in 2014 as a result of a new wave of protests against the government, as the return of a “radiation specter.” This specter redistributes the strength and intensity of the performance and reinforces its dissidence. Castro’s third line of analysis comes from Gilles Deleuze’s reading of the Marquis de Sade and Sacher-Masoch, and proposes to read Lamezuela (2012) as a sadomasochistic performance whose ultimate function is to humiliate the father/state.

The four subsequent essays focus on two exhibitions in which the artist explores and challenges different dimensions of the Simón Bolívar cult in Venezuela: “Acción y culto” (2013) and “RAW” (2015). Cecilia Rodríguez Lehman examines the dialogue that Castillo establishes with attempts carried out under the Hugo Chávez government to reconfigure the national imaginary through the destruction, manipulation, and renovation of several symbols that constitute the iconography of the fatherland. In her reading of Sísifo (Sisyphus) (2013) and El beso emancipador (The Emancipatory Kiss) (2013), works that were part of the “Acción y culto” exhibition, and Slapping Power (2015), which was part of “RAW,” Rodriguez Lehman argues that Castillo’s work destabilizes the construction process that casts Bolívar as father of the nation and as political instrument. This is achieved through a process of appropriation that immerses Bolívar in mass culture and turns him into a passive actor, a “secondhand hunk” who, consequently, loses his aura, thus revealing the “fictional nature of said memory, its arbitrariness and its fragility”.

Rebeca Pineda Burgos’s essay, on the other hand, focuses on El beso emancipador (2013), a performance she analyzes through the notion of habitus that Jon Beasley-Murray condenses in his reading of Pierre Bourdieu. Pineda Burgos emphasizes the repetition that is staged not only in El beso emancipador (2013), but also in the criticism that both Castillo and her performance received from government supporters. This repetition re-visibilizes the habits that function as mechanisms of state control, and which, according to the author, are often invisible precisely because of their banality. Faced with these habits, Castillo presents her body as one that has been intervened upon by the state, but in which there is a potential that escapes and manages to resist the state’s control. This happens thanks to the decontextualization that is possible in the artistic space of performance. A certain estrangement from the habitus takes place there, a critical look and a physical resistance that is also political.

In her reading of Detritus (2015) (which was part of “RAW”), Sara Garzón presents Castillo’s work as an act of political iconoclasm that questions the glorification of the figure of Bolívar by challenging his masculinity and the apparent stability of its ideological significance. Particularly productive is the author’s theoretical proposal regarding what she calls State repertoires, which she defines as the set of performative rituals and political discourses that are the base of national ideologies and the love of homeland. According to Garzón, Castillo intervenes and modifies said repertoires through different forms of monumental destruction, which show the fragility and arbitrariness of the iconic status of Bolívar. Said acts of destruction imply a mockery of masculine sensitivity, thus humanizing the sacred body of the Liberator. In this way, Castillo shows how national iconographies are converted into instruments in service of certain ideological purposes, and how they manifest not only as political projects, but also as behaviors and beliefs.

The reading proposed by Irina Troconis highlights the materiality of two of the works that are part of “RAW”: The Unnamable (2015) and Demagogue (2015). Troconis suggests that Castillo’s decision to use raw clay in these works––and in her work in general––emphasizes the malleability of the bodies of the past and, therefore, our ability to intervene and give shape to the narratives that bring them into the present and legitimize their authority. By transforming the bronze statue or monument into precarious figures made of fragmented, moist, and unstable clay, Castillo grants us access to the making of the past, and invites us to ask ourselves not only what we owe our dead, but also what they might owe us. Troconis also argues that the aesthetics of raw clay reproduces the materiality of the flesh and, specifically, of the corpse, which restates the relationship with the figure of the caudillo as a necrophilic one. This simultaneously generates attraction and disgust, and allows us to adopt some critical distance from the authority granted to the spectral figure of Bolívar and the Bolivaroids that came after him.

The volume finishes with Diana Taylor’s analysis of Marx Palimpsest (2018), which was performed on October 26th in the Coatlicue Lounge of the Hemispheric Institute in New York City. Taylor gives an account of each of the movements made by Castillo’s body––and of the physically exhausting work behind them––when she writes the Communist Manifesto on the walls and then crosses out certain parts of it. In this slow and laborious process that moves from order to disorder, from coherence to incoherence, Taylor reads a critique of the reduction of the female body to the body of the unnamed worker without identification––nothing more than a machine of production and reproduction––in struggles both for and against Marxism. Likewise, she reads an effort on the part of Castillo to recover that lost agency, to re-empower the female body through a quiet resistance that succeeds in “taking Marx down.” This process of decomposition, however, is also a gesture that does not stabilize, but instead is open to interpretation and speculation, thus creating a space of resistance directed not toward this or that figure from the Left or Right, but toward the oppression born out of ideological manipulation.

Although some of the essays in this volume study the same performances, each of them provides a unique critical perspective. Castro’s reading proposes an analysis that puts Castillo’s work in dialogue with the problem of fetishism in psychoanalysis; Rodríguez Lehman and Garzón place the artworks in a wider social and cultural context, which considers the political instrumentalization of art, as well as the manipulation of national symbols by the state; Pineda Burgos highlights the political potential of the performance to question the banality of the state’s mechanisms of control; Troconis analyzes the relationship between memory and materiality; and Taylor reflects on the work of the artist as a gesture that criticizes and resists ideological manipulation, wherever it comes from and without constraint. Taken as a whole, these essays reflect not only on the irresistible polysemy that is played out in Castillo’s work, but also on the latter’s hemispheric relevance.

Castillo’s tongue is a powerful organ that dismantles the language of power by rematerializing what it licks, bites, hits, and masturbates. To do this in one of the most violent countries in Latin America is no small thing. Deborah Castillo gives a body to the state, remembering, forever, its fragility, and ridiculing the eloquence of its pompous performance. For the first time ever, Radical Disobedience brings together a series of critical texts on the work of Castillo and, in doing so, this volume critically reflects on the performance of political power and the power of performance as an act of radical disobedience.