unmentionable Man. 2015.

Three of the white gallery walls are covered with lines of writing, line after straight line of neatly spaced text. Written in thick, charcoal pencil, the cursive looks like the tidy script that school children practice in lined workbooks where two lines control the height of each letter, the capital and lower-case as well as the ascenders and descenders. “El movimiento proletario es el movimiento espontáneo de la inmensa mayoría en provecho de la inmensa mayoría” (“the proletariat movement is the spontaneous movement of the vast majority for the benefit of the vast majority”). Key points from Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto have been painstakingly copied out on the various walls. A total of ninety-one fragments comprise the performance. First performed at the Carmen Araujo Gallery in Caracas (2016), the number of fragments and the duration of the piece (between forty-five minutes and an hour and a half) vary according to the size of the space.

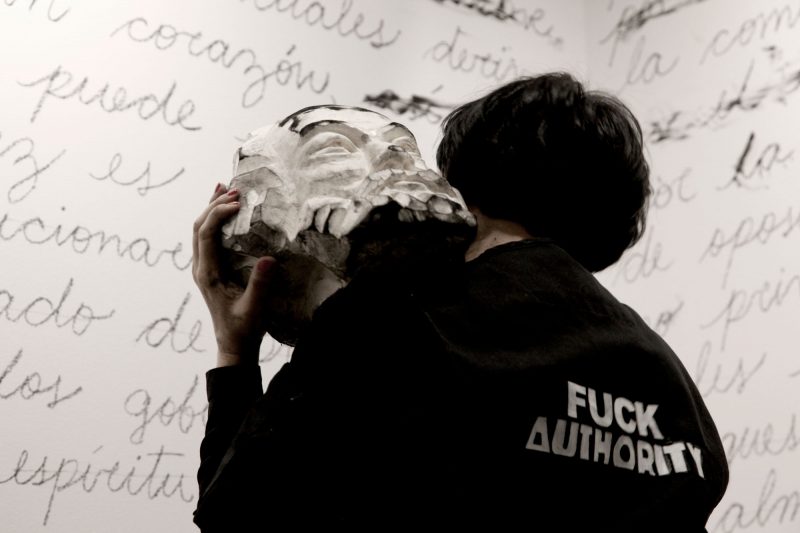

Dressed in black pants, shirt, and heavy black shoes, Deborah Castillo, a performance artist from Venezuela, enters the Coatlicue Lounge at the Hemispheric Institute, which serves as a small exhibition space. The audience sits on the floor or crowds against the back walls. She picks up the large, very heavy eraser in the shape of Marx’s head that stands on a white gallery stand in the middle of the room.

Her bright red fingernails on Marx’s head offer the only color in this black-and-white performance. Without acknowledging or interacting with the audience, she presses the eraser methodically over some of the words and phrases in each sentence. The first line on the gallery wall, “El movimiento proletario es el movimiento espontáneo de la inmensa mayoría en provecho de la inmensa mayoría” becomes “El movimiento proletario es el movimiento espontáneo de la inmensa mayoría en provecho de la inmensa mayoría.” “The proletariat movement, for the benefit of the proletariat,” is now simply gibberish, “the movement the vast majority.” She reduces the Manifesto to nonsense: “Capital is therefore not only personal; it is a social power” becomes “Capital a personal power” [“El capital no es, pues, una fuerza personal, es una fuerza social.”]. The walls show the move from coherence to incoherence, from order to disorder, from one system of thought/discipline (depicted in the carefully measured writing) to the erosion of thought. Yet with all of the redactions, it’s surprising how the text continues to read more or less fluidly. If one weren’t concerned with coherence, it might even sound plausible. Political ideologies and discourses, Castillo reminds us, are easily morphed to alter meanings under the guise of continuing the status quo. Marx’s palimpsest, however, still reveals the traces of the old.

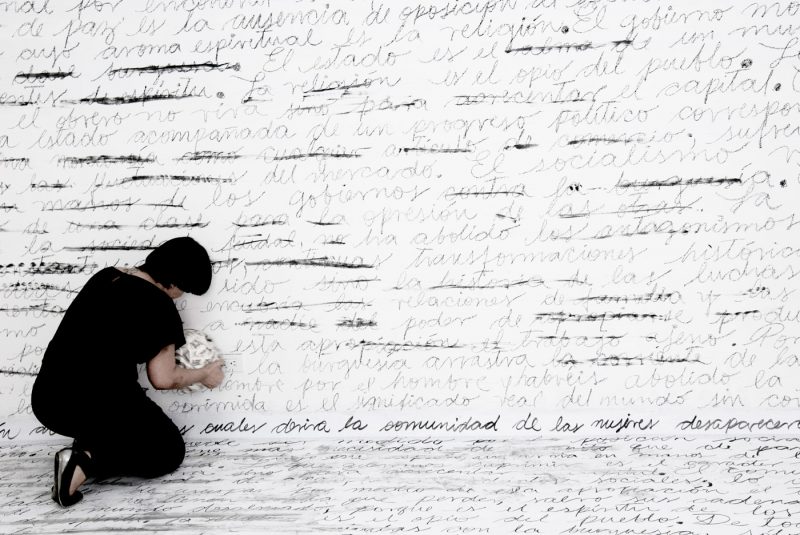

Castillo, a small, strong woman, labors under the burden of the Marx eraser/head that weighs some thirty or so pounds. As her attitude and physical toil demonstrate, this is labor, physically taxing work. Standing on a small bench, she stretches the eraser to reach the top lines. Kneeling, she holds the heavy weight on her knees as she buffs it against the words closest to the floor. She grows increasingly exhausted as she pushes the rubber head from line to line down the first wall, then tackles the second, then the third, erasing what exists to undo Marx and create the uses and appropriations of Marx in unbounded capitalism. Castillo walks around the room, examining the texts and the excisions. Here and there she’ll rub out an additional word or phrase, step back, and continue to scrutinize the wall. When she’s satisfied, she places Marx’s darkened head on a white gallery stand in the middle of the room, and leaves. The messy walls remain to tell the story of decomposition.

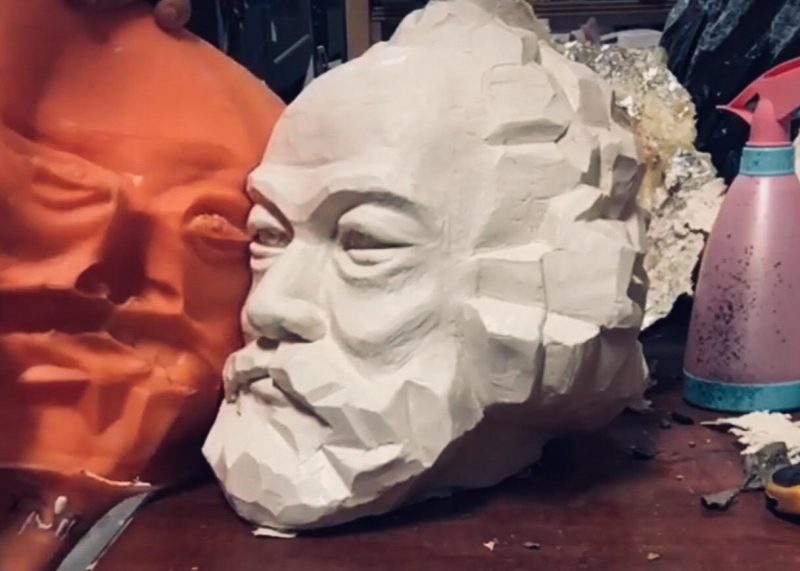

Marx Palimpsest, like several other of Castillo’s pieces, starts long before the live action in front of the audience begins. She sculpted Marx’s head out of rubber and developed the formula to make it into the consistency of an eraser in what she calls “a very artisanal process” (“un proceso muy artesanal”). Days before the performance, she created a grid of the lines with thread.

Then she wrote out the text. On the day of the performance she laboriously redacts the text in front of the audience who enters into a slow, almost trance-like state watching the slow, careful, repetitive movement of erasure. In exhibition spaces such as Hemi’s, the smudged walls with blurred writing, the smudged head on the stand, and the video of the performance continue to perform long after the live performance is over. Castillo’s Marx Palimpsest, then, reveals the history of the making and unmaking of the performance even as it might convey the history of the uses and abuses of ideology. The history of practice and the practice of history, she suggests, is very messy process.

What to make of the fact that Castillo uses her own small, female body as an instrument of elision? Unlike several of her other performance pieces—many of which feature her as the sole actor—this one does not have an explicit erotic dimension. In Lamezuela (2011), El beso emancipador (2013), Demagogue (2015), and The Unnameable (2016), Castillo enacts the seduction at play in authoritarian forms of power. In Lamezuela, she slowly licks the boot of the military man who stands still, erect, and at attention. In El beso emancipador, she slowly, voluptuously runs her tongue over the mouth, nose, chin of the golden bust of Venezuela’s national hero, Simón Bolivar, the “liberator.” In Demagogue, she pulls on the nose of the clay sculpture of a military male until the nose distends into a grotesque penis. In The Unnameable, staged for video, a naked Castillo runs the male’s dead grey hands (made of clay) caressingly over her face, neck, and supposedly down over her body.

However, the military male—the soldier and the national hero (Bolivar)—demands submission. The “orgiastic transactions” that Susan Sontag (1983) describes “between mighty forces and their puppets,” carry their own gendered, seductive pull (316). “The domain of eroticism,” Georges Bataille (1986) noted, “is the domain of violence, of violation” (16). And the military purportedly have exclusive rights to both. The female, Bataille continues, occupies the space of victim (18). Castillo reverses the agency in these performances, usurping the erotic power and using it against the military male. She sensually licks, rubs, and caresses. The stiff, ever upright, phallic self-containment of the male is undone by the insistent incursion of the female, as her tongue, hands, face insinuate themselves into and over him. He is violated, de-authorized. She assumes power. In Marx Palimpsest, however, Castillo uses her gender and sexuality more guardedly. The female body, though central to the performance, remains controlled, clad head to toe in workers’ garb. In a way, this suggests that the struggles for and against Marxism reduce the female to no more than a worker, a laborer who contributes her labor un-noted and un-marked. The body is an engine of production and reproduction; nothing more. And yet, as an act of quiet resistance perhaps, she authors the decomposition; she takes Marx down.

Much as in her other performance pieces, Castillo’s Marx Palimpsest continues her theme of tearing down idols. Painstakingly, in each case, she sets up the scenario—the hero’s head sculpted in clay, the military male’s boot readied for the licking, the meticulous laying out of lines for the writing of the fragments—only to destroy or deface it. These various pieces enact different affective modalities emanating from her body: her contempt in Demagogue; her fury in Slapping Power in which she slaps the military man’s head, made of slightly wet clay, until it falls of his shoulders; her eroticism in Beso; her measured, slightly resentful attitude of a worker in Marx Palimpsest.

Each performance relies on the repetition of one key gesture—the slapping, the licking, the redacting. Gesture, here, performs not only between bodies and things (Castillo and Bolivar’s bust, or Marx’s text), but also across various expressive arenas. From Medieval Latin gestūra, gesture is a mode of action. It refers to a movement by the body intended to express a thought or feeling, an emotion, an idea, an opinion, or a political posture. The embodied, communicative, affective, and political dimensions of the word open up an expressive field of possibility, which ranges from the empty impulse (a token or meaningless gesture), to the small move (erasing a word), to the accomplished act (Castillo’s performances). Gestures can be both fleeting expressions and iterable, quotable enactments that cite previous acts and positions—everything from Brecht’s (1964) gest or gestus (attitude) to the repeated slap (198). They often accompany speech, but they are not reducible to verbal language. They capture the many facets and forms of expression that make up a communicative act.

“Gestures,” unlike other acts, as Vilém Flusser (1991) noted, “are movements of the body that express an intention” but “for which there is no satisfactory casual explanation” (1). Why does Castillo slap the clay bust or erase the text? There is no clear-cut answer. Unlike simple acts—she moved her hand from the flame to avoid being burned or she swatted the mosquito on her arm—gestures rely on interpretation and speculation. Art functions in this realm. While Castillo’s gestures are deliberate and clear, their meaning and therefore that of the performance remains ambiguous, open to analysis and discussion. Why does Castillo erase certain words? What does she find oppressive? Is it Marxist ideology and the ways in which it has been used and misused in Venezuela and perhaps Cuba? Or perhaps the erosion of that ideology beyond recognition to serve contemporary political needs? Some might object that Castillo targets the leftist luminaries for critique—Bolivar, Castro, Chavez and of course Marx. But the pieces might as powerfully reflect the oppressive use to which these figures have been put in Venezuela, the brutal contradictions these heroes and ideas have covered over. The “Fuck Authority” on the back of her shirt suggests she too is among the many left out of the bourgeoise’s exclusive hold on well-being that Marx and Engels critiqued. Yet the disciplined handwriting of the Manifesto that fits obediently into the clearly demarcated lines signals that the systems of thought that transmit and rely on Marxism also weigh on populations. Part of the burden might be both the institutionalization and debunking of ideologies, perhaps even the debunking that occurs through the very act of institutionalization. Is Marxism oppressive? Or is the elision oppressive? Instead of an either/or, this might well be a case of the both/and.

Castillo refuses to clarify the ambiguity. She might take down idols, but she will not shut down interpretation and analysis. Rather, she continues to slap, lick, erase and otherwise contest oppression in its many, at times contradictory and conflicting guises.

Works cited

Bataille, Georges. 1986. Eroticism: Death & Sensuality. Translated by Mary Dalwood. San Francisco: City Lights.

Brecht, Bertolt. Brecht on Theatre 1947-1948. 1964. Edited John Willet. New York: Hill and Wang.

Flusser, Vilém.Gesture. 1991. Translated by Nancy Ann Roth. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Marx, Karl, and Engels, Friedrich. 2008. The Communist Manifesto. London: Pluto Press.

Sontag, Susan. 1983. “Fascinating Fascism.” In A Susan Sontag Reader. New York: Vintage Books.